- Home

- Lloyd Jones

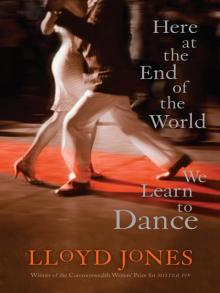

Here at the End of the World We Learn to Dance

Here at the End of the World We Learn to Dance Read online

Praise for Lloyd Jones and

HERE AT THE END OF THE WORLD WE LEARN TO DANCE

Shortlisted for the DEUTZ MEDAL FOR FICTION

at the 2002 MONTANA BOOK AWARDS

‘Just like the tango itself, heartbreaking and exhilarating…

Jones has solved something that’s notoriously difficult:

how to write about music so that the words

themselves express its character.’

NZ Herald

‘Totally arresting and compelling all the way through.’

Radio New Zealand

‘Lloyd Jones reinvents himself in each new novel…It reads

like the effortless soar and dip of a grand piece of music.’

Age

‘Jones’s prose is faultless.’

Publishers Weekly

‘Its fable-like quality is spellbinding; the depth of

its insights compelling.’

Canberra Times

‘Gentle, whimsical…with a lot of understated humour and

a strong sensuality. Jones’s writing is easy and sophisticated,

reminding me of Steinbeck at his humorous best.’

Age

Praise for MISTER PIP

Winner of the

2007 COMMONWEALTH WRITER S’ PRIZE

Winner of the 2008 KIRIYAMA PRIZE

Montana Awards:

READERS CHOICE AWARD,

MONTANA FICTION AWARD and the

MONTANA MEDAL FOR FICTION OR POETRY

Shortlisted, MAN BOOKER PRIZE, 2007

‘Mister Pip is a rare, original and truly beautiful novel.

It reminds us that every act of reading and telling is a

transformation, and that stories, even painful ones, may

carry possibilities of redemption. An unforgettable

novel, moving and deeply compelling.’ GAIL JONES

‘As compelling as a fairytale—beautiful,

shocking and profound.’ HELEN GARNER

‘Jones has done something very difficult with this

novel: he has taken a recent and brutal piece of

contemporary history and has told a story that not

only reveals these events to the wider world but also

shows what they mean in the larger and more abstract

field of human behaviour.’ Sydney Morning Herald

‘Poetic, heartbreaking, surprising.’ ISABEL ALLENDE

‘The accessible narrative, with its direct and graceful

prose, belies the sophistication of its telling as

Jones addresses head-on the effects of imperialism

and the redemptive power of art.’ Booklist

‘Lloyd Jones brings to life the transformative power

of fiction…This is a beautiful book. It is tender,

multi-layered and redemptive.’ Sunday Times

‘A bold inquiry into the way that we construct

and repair our communities, and ourselves,

with stories old and new.’ The Times

This wonderful, sad book wraps complex themes—faith,

race, imperialism and growing up—in a thrillingly

accessible package, returning again and again to

stories and the hope they can bring.’ Guardian

Lloyd Jones was born in New Zealand in 1955. His best-known works include Mister Pip, winner of the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, The Book of Fame, winner of numerous literary awards, Biografi, a New York Times Notable Book, Choo Woo and Paint Your Wife. Jones lives in Wellington.

Here

at

the

End

of

the

World

We

Learn

to

Dance

LLOYD JONES

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The paper in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William St

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © Lloyd Jones 2001

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Penguin Books (NZ), 2001

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company, 2008

Design by Chong Weng-ho

Typeset by J&M Typesetters

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Jones, Lloyd, 1955-

Here at the end of the world we learn to dance / author, Lloyd Jones.

Melbourne : The Text Publishing Company, 2008.

ISBN 9781921351556 (pbk.)

NZ823.2

To my family

‘The tango is man and woman in search of each other.

It is a search for an embrace, a way to be together.’

JUAN CARLOS COPES, choreographer and dancer

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

1

For eleven years an elderly man with a silver-knobbed cane visited Louise’s grave with flowers. He came every Saturday with a plastic bucket, brush, cleaning fluids and a fold-up canvas chair. He was always impeccably dressed for the occasion. A black blazer, white slacks. A bright red flower in his buttonhole drew attention to his snow-white hair.

The year before his death it was his habit to visit the cementerio at La Chacarita with his ten-year-old granddaughter. While he sat by Louise’s grave fanning his face with his fedora the granddaughter would go and stand in line with her plastic bucket and the other mourners at the water taps.

He had his own car, but for this particular excursion Paul Schmidt favoured the bus. The conductor helped him down the steps. He didn’t experience any of the same uncertainty or hesitancy on the dance floor. He could always count on the same instruction,‘Careful of the traffic, Señor.’ With a dismissive grunt Schmidt would set off across the busy road for the flower stand on Coronel Diaz.

For someone with a huge deception at the centre of his life, Schmidt prided himself on cultivating many small loyalties. That particular bus conductor, for instance. Another was the Paraguayan flower vendor from whom he always bought blue irises.

One Saturday morning a special flower of a competing vendor’s display caught his eye—buttercup and broom—arousing in him an old memory. With some difficulty, as the bus was still moving, he stood out of his seat and stumbled past the knees of the woman sitting next to him.The bus lurched, and as his hands pawed at the dangling hand grips his cane c

lattered into the aisle. He didn’t give it a second thought. Later, the conductor would recall Schmidt stooping to catch the receding view of the flowering broom in the back window, his hand on the shoulder of an unprotesting woman to steady himself.

At the next stop (not his usual stop) Schmidt struggled down the steps. The conductor caught up with him and handed him his cane. The old man gave it a brief regard and took it without thanks. The conductor smiled.They had an understanding, and in a manner of speaking had forged a friendship based on two predictable moments in each other’s life. One, where the Señor picked up the bus and where he got off. The other significant moment arrived in the week leading up to Christmas when the Señor would give him a box of expensive cigars. It was always a last-minute thing. As the bus slowed down to his stop the cigars would be quickly produced and given without fuss as if he had no further use for them; for his part the conductor always received the cigars with noises of gratitude and false humility.

Now in the window of the bus he followed the old man’s progress across the wide and busy road. He saw him poke his cane at the oncoming traffic. Later, the flower vendor would say that the Señor’s ‘eyes, face and memory were so closed around his flower display’ (not merely the yellow flowering broom, note, but his flower display), ‘that he did not see the bottle truck coming the other way.’ Meanwhile, from the bus window a hollow warning rose in the conductor’s throat. He closed his eyes to avoid the final moment of impact. It was a story he would tell many times. First, the distraction. The old man’s sudden rush of blood to the head. Then, his wilfulness. The broken routine and—as a result the loss of the cigars at Christmas. It was a cautionary tale.

2

In death there are no secrets. At La Chacarita, the wealthy are laid to rest in huge pharaonic tombs; mausoleums are styled after famous chapels. Sculpted angels and lute-players pirouette in cement and plaster. Biblical scenes are lavishly carved out of stone. If a rich life must be seen to continue on into death the same could be said of the poor who are parked end to end, on top of one another, sandwiched in to the massive walls of vaults. These older burial walls form inner walls of the cementerio. The newer vaults have been constructed by a mall developer. Bodies are stacked in galleria after galleria, and stairways descend two and three floors into the earth to work benches and cemetery workers in blue overalls shouldering brooms. The air is closed with the sickly fragrance of old flowers stuck in the coffin handles.

There was almost nothing that Schmidt could not have afforded. His widow had imagined a small family crypt, perhaps with some orchestral theme to symbolise the family business interests.

Instead, to his wife’s great surprise, and the family’s, Schmidt’s final instructions were for a simple burial alongside his devoted shop assistant; a plain and quiet woman, the ‘English woman’ whom Señora Schmidt had known simply as Louise.

They had exchanged pleasantries. Proper conversation had always required extra effort. The woman’s Spanish was at best infantile. When she shopped she pointed at the items she wanted, extending the word on the end of her finger. Now that Schmidt’s wife tried to recall all those other times they had met the occasions were so brief that nothing particularly telling or revealing had stuck.

Once, during a summer storm, at her insistence Schmidt had dropped the ‘shop assistant’ off home in a taxi. She remembered glancing up at a grey building with a pink and blue plaster relief (a rosette, she seemed to recall) and the shop assistant’s face suddenly dropping into the window to thank her for this kindness. Her hair was wet and unruly; her face washed out, a dark smear of eyeliner running from a corner of her eye. No one would ever say she was a classic beauty.

Louise had been dead for eleven years but one elderly woman, a former neighbour, remembered ‘the English woman’. She recalled that she had kept to herself. The old woman shouted: ‘She could not speak.’ And no, she did not seek friendship. ‘What about visitors? Did she have many?’ The neighbour’s face grew thoughtful. Schmidt’s widow briefly considered offering money, but then the woman spoke: ‘Many, no. Not many. But there was one…’ And she began to describe her late husband, his shock of white hair, his smooth face, his chestnut eyes, the cane, his careful dress. ‘You know how it is, Señora. Some people end their days having conquered time. Others are still running on the spot as they leave this world. The Señor was of the former category.’ The conversation took place on the landing. A leaky tap could be heard along the way. It was such a rundown place. Her husband had always been so fussy. She couldn’t place him here, on this landing. She began to walk along the hall. She stopped and looked back to check. ‘This room at the end?’ The woman nodded. ‘Si, Señora, that is the room.’ She thought, he must have seen this view, the same cold angling light in the end window, the same bare floorboards creaking under his feet. But what must he have felt? Excitement? A lift in his heart? The neighbour caught up with her. ‘Señora, I can show you the courtyard if you wish. The gentleman and the foreign woman sometimes sat in the garden beneath the lime tree. The tree is no longer, I regret to say…’

Schmidt’s widow shook her head. She had seen and heard enough. She was ready to leave.‘There is one other thing,’ resumed the neighbour. She began to describe the day the landlord’s men had shown up to cart away the dead woman’s possessions. She suddenly looked mischievous and edged her face closer to confide. ‘I snuck my head in for a look. I was curious too.’ Well, there was little to remove. A record player, a stack of record albums, some articles of clothing, a pair of black stilettos, ‘the kind worn by those who dance at the Ideal.’ The widow had friends who danced there. Now she wondered if they had seen her husband with the shop assistant and chosen not to say anything. The neighbour continued. She was used to cluttered rooms herself, but in the dead woman’s flat you noticed the floorboards. They stood out. Their long run and the ‘scuff marks’ in the middle of the main living area. The widow felt her eyes smart as she pushed out the next question, but she had to ask. ‘She and the Señor liked to dance? Is this what you are telling me?’ The neighbour made a grand display of her hands. ‘Dance? They dance and they dance. Oh, how they dance. Then they sit in the garden to rest, then they dance some more. The woman did not speak. She dance only.’

3

No one passes through life unnoticed. The panaderia where she bought her bread sticks. The bus driver. The news-stand where she bought the English-language Buenos Aires Herald. And, of course, there was Max. Homosexual Max. His face tilted to receive kisses on both cheeks from his regulars. Max bulging like an overcooked soufflé inside his waiter’s jacket. Max with his hairless chin. His small appreciative eyes glowing inside his spectacles. His body was found on the other side of Avenida Moreau de Justo in a stagnant pile of plastics and bottles, nudging against a bloated pig by the boatman’s pier.

In the café where Max worked, small children with grown-up faces on the end of spindly bodies placed cigarette lighters on the tables of drinkers late in the afternoon. The drinkers waved them away like blowflies.They tapped the ends of their cigarettes into the ashtrays and resumed their thoughtful answers. A balding man, yes? No. No one could remember Max. For thirty years he worked behind the blinds at La Armistad, in the city neighbourhood of Montserrat, yet no one could remember his name.

Time is cruel, though necessarily so. The world has to make room for so many names.

In the 1940s, a young man with a large pink birthmark on his neck used to deliver coffee on a silver tray to Schmidt’s staff on Coronel Diaz.

Years later the birthmark has faded and crumbled like an old head of agapanthus above a frayed and brackish collar. His eyes slope up to his crinkled forehead while he thinks back.

‘Si. The Señora always ordered a short black.’

‘A short black?’

‘Si, espresso.’

‘That is all?’

The man shrugged; his head and shoulders rose, his lips pursed; his eyes sloped down into the pit of memory.<

br />

‘Sometimes a pastry,’ he said.

‘What kind of pastry?’

‘Señora, it is a long time ago.’

Louise’s friends, the ones she trusted and listened to and confided, day in, day out, year after year of lonely exile, are to be found in several rooms of a restored palace on Piedras and Independencia. Troilo. Goyeneche. Gardel. Each with their own room. You look up at the walls with their photographs. Their personal belongings are religiously displayed; on their own they are not particularly interesting—but that they belonged to Gardel is everything. So you find a long glass tube that contained the singer’s toothbrush, his silver shoe-horn, a ring engraved with his image that the loving son gave to his French-born mother, his French-tailored collars, his cane, his silk lengue; and since the smallest detail is not to be overlooked, the ticket punch from window Number 10 where Gardel used to place his bets at the Palermo racecourse is included.

Then there are the photos. Gardel with his film star looks; his ever present smile, the slicked-back hair in the style he pioneered. In a group photograph you can tell which is Gardel simply by looking for the focal point. He is the one smiling his radiant smile, the grateful beneficiary of a once-in-a-century singing talent and universal love.

Louise arrived in Buenos Aires a few years before Gardel’s plane crashed in Colombia. In all probability she was one of the hundreds of thousands who formed either side of his funeral procession up Corrientes to La Chacarita. The procession passed through the working-class neighbourhood of Almagro where she lived. She experienced this and other major historic events: the revolution, the war, the rise of Juan and Eva Perón, Evita’s death and a funeral procession even larger than that which saw Gardel on his way. Defenders of Gardel’s unimpeachable reputation are quick to point out that by the time of Eva’s funeral, Buenos Aires had grown to a city four times the size it was in Gardel’s day. In any case, these events are mere backdrop. They don’t belong in Louise and Schmidt’s story. The composers, the singers and the bandoneon players were more influential.

Mr Vogel

Mr Vogel The Man in the Shed

The Man in the Shed Mister Pip

Mister Pip Hand Me Down World

Hand Me Down World Biografi

Biografi Paint Your Wife

Paint Your Wife Here at the End of the World We Learn to Dance

Here at the End of the World We Learn to Dance My First Colouring Book

My First Colouring Book Mr Cassini

Mr Cassini See How They Run

See How They Run A History of Silence

A History of Silence The Book of Fame

The Book of Fame